|

| My First Astrophoto - Dec 15, 2010 |

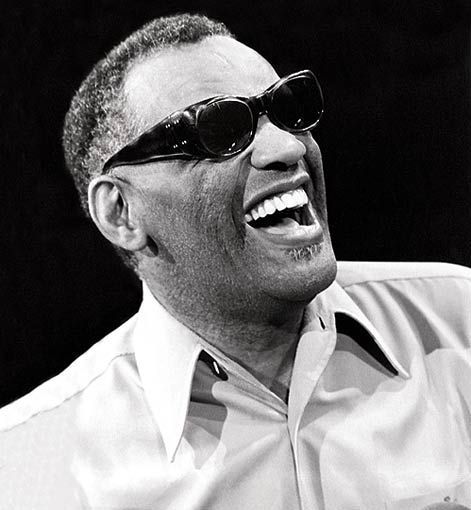

Feast your grubby little peepers on that ridiculously amazing piece of astronomy history right there to the left - The Greatest Astrophoto Ever Taken. Enlarge it, print it out and save it so you can tell your granchildren about it and how you weren't there. I will accept no argument in this discussion. I have decreed it's the greatest ever, and thus it is so. It's also the greatest one ever captured since because it's mine and it's my first. Anyone who has ever taken up this fantastic hobby depraved obsession knows what I'm talking about. Aesthetically and technically (let's not forget morally and emotionally too) the image is simply terrible. Look at it. It's a poorly color balanced, out of focus, partly trailed shot of the entire constellation of Orion. But it's my first. I still remember the rush after stacking up all those images and seeing something that looked sort of like stars and a little blur of M42 to go along with it. That was one year ago today as I begin writing this. As this day has approached I've been reflecting on how far I have come in many ways and how little I've learned in others.

How it all started

In my professional life I've worked in a contract/consulting capacity for all of the last twelve years. In that time I've spent an enormous amount of time on the road away from home working at client sites and kicking it in various hotels all over the United States. At times it has been a major grind and trying on my family but it has been relatively lucrative and it provides a good life for my amazing family. This was partially the reason that I gave up amateur astronomy back around 2005 - there simply wasn't enough time. If I left my wife and girls to go out observing for a weekend I felt guilty for coming home from the airport and disappearing to the desert, only to reappear in a couple of days and head back to the airport. Fast forward to 2010 and my girls are much older now - teenagers and beyond. I had been itching to jump back into the astronomy game and I had always kept astrophotography on my list of things that I must do before I die. At the time, I was still on the road every week - working in Las Vegas. Since I've never been one to gamble and my Irish liver threatened long ago to defect to another nationality if I didn't give up drinking, life in Las Vegas was quite monotonous. That's the real truth about my glamorous, rock star consulting lifestyle. There are huge amounts of time where it's truly downtime and there's nothing to do.

I began to think about astrophotography and saw what other amateurs were able to do with a standard DSLR camera. I had some Photoshop experience and realized pretty quickly that this could be the answer to my on the road boredom. If I started in some astrophotography on the weekends, I'd have a bunch of data to crunch, process and massage into a new website that would undoubtedly be called the Mike Picture of the Day. After I captured the greatest astrophoto ever (shown above), the hopeless addiction took hold and it's been a year of thoroughly enjoyable madness and thoroughly maddening joy.

|

| M45 - Captured with my Canon 60D piggyback mounted on the CGEM mount. This was the 3rd image I captured. |

I missed having a go-to telescope so I had this awesome plan where I would buy a CGEM 1100HD telescope for visual observing and also use it to begin dabbling in some piggyback astrophotography. Dean at Starizona called Celestron directly while I stood there and secured the telescope for me and said it would be four or five days before it came from California. I made plans to return the next weekend and pick up the telescope. It was also during this visit that Dean suggested I should consider Hyperstar as a good way to get into imaging. I was able to resist his suggestion for now - but that would change soon enough. The next weekend saw the capture of my second astrophoto which was my first shot with a camera on a motor drive - piggybacked on the new CGEM mount.

|

| M42 Region captured with a telephoto lens |

Imaging already dominated my thought process. It had become like a drug and I spent great amounts of time trying to figure out where I was going to get my next fix. I ended the year of 2010 by heading west into the Arizona desert for my first dark-sky imaging session to the Saguaro Astronomy Club's Antennas site. Everyone else in the astronomy club had opted out of the weekend because of the extreme cold predicted in the weather forecast and the lack of shelter available. I had been there before and thought, how bad can it be? One other brave soul joined me - and he bailed on me because of the cold at about 10:00 pm. I held on until about 2am, spending some time in my vehicle with the heater running while the camera did its thing outside. I brought home a telephoto shot of the M42 region for my efforts. I also realized that the 11" Edge HD optics were not going to be seeing any real use as a visual platform - imaging had stolen my affections. If a 75-300mm zoom lens could give me this kind of result, what would happen if I put the 11" telescope itself to use?

Enter the Hyperstar

|

| Horsehead Nebula via Hyperstar My first Hyperstar image - 32 x 2 minutes with a Canon 60D at f/2 |

I ordered the Hyperstar in early January and waited impatiently. Very, very impatiently for it to come. It showed up at the end of January and I took a few exposures in the backyard just to familiarize myself with its use. I didn't have the ability to autoguide at this point and knew that I wanted to go as deep as I could with my images anyway. So when I returned to the Antennas observing site at the end of January, I took great care in making sure that I nailed down the most accurate polar alignment I could. This was my "real imaging trip" and I put a lot of effort into planning. I've since come to learn that this is a key to good astrophotography - planning and discipline. I abandoned both for awhile with the expected results of bad astrophotos. I planned to start with the showpiece objects - M42, The Horshead nebula region and the Rosette nebula. I made a plan to shoot 32 exposures of each at 2 minutes per sub exposure at ISO 1600 with my Canon 60D. As soon as the first frame of the first exposure of the Horsehead region downloaded to my screen, I made an audible and very un-Christian expression while hunched over my laptop on the observing field. Completely blown away by the images I couldn't image often enough. I spent every night while on the road soaking up knowledge. I lived for a time on the Cloudy Nights imaging forum and I picked up Adam Block's Photoshop Tutorial DVD which I found to be extremely helpful and interesting.

|

| NGC 5139 - Omega Centuari 32 x 45 Seconds @ ISO 1600 & f/2 |

I made plans in April to participate in my club's Messier Marathon - only I planned to image all 110 objects in one night via Hyperstar and hand in a DVD of completed images prior to leaving the observing field. Well, nature had other plans. Our Messier Marathon was pretty much clouded out. In March I did a dry run to test all of the scripting that I had put together and was able to capture 71 Messier's before 2am. Using Hyperstar I was able to capture and stack ten 30 second subs of each object which gave enough signal to noise to present some pretty nice images. Like I said, the real marathon in April was clouded out but I managed to get a shot of Omega Centauri that I still think is my favorite astrophoto so far.

The Dark Times

Soon, my thirst for knowledge and my insistence on pushing the envelope at ludicrous speed began to work against me. I wanted to do everything and I wanted to do be doing it now. This led to a series of equipment purchases that were just done too quickly. I didn't really incorporate each new piece of imaging equipment into my overall workflow before I was trying jam in yet another piece.

- March - I added a QHY5 camera and Kwiq Adapter from KW Telescope to begin autoguiding.

- March - Upgraded to Maxim DL Pro to use the autoguider as part of my overall capture suite.

- April - Upgraded to a cooled CCD camera - a QHY8PRO from Astrofactors.

- May - Struggling with autoguiding, I'm back and forth between Maxim DL and PHD Guiding. In the end I have discovered that they're both great products - that the user (me) is usually the problem.

- June - In an effort to gain more weight capacity in the hopes of moving to imaging at prime focus I upgraded the mount to a used Celestron CGE.

- June - Thinking that the guidescope (my 9x50 finder) was the problem I added an 80mm f/7.5 guidescope.

All during this time I began to experiment with every form of technique you can think of - dithering, mosaics, plate solving, drizzle stacking, etc. I learned how to do all of it in the most basic form of that phrase. I didn't learn any of those techniques or my new equipment well though. There were a handful of successful images, but by and large it has been a lot of frustration that has been documented pretty thoroughly in these pages over the last 6 months. In that time I don't think that I've really improved my skills all that much and the ratio of good to failed images has been unacceptably low.

Celebrating the first year

I wouldn't trade this first year for anything. Overall, it's been a resounding success and has renewed my passion for astronomy in a way I didn't think was possible. I've also learned that I need to take a step back and properly incorporate all of that equipment that I listed above - one step at a time. I've documented the struggles that I've had over the last couple of months with my telescope mount here and here. I've decided to take the equipment one piece at a time and really get it incorporated into the overall workflow before tackling another piece of the puzzle. Yesterday I picked up my telescope mount from Ed Thomas at Deep Space Products after having a Hypertune service done. Since Ed is local to me I was able to drop my mount off and pick it up when he was finished. I haven't had a chance to thoroughly test the results, but the five minutes that I spent slewing it around last night showed that it seems to be vastly improved. Stay tuned for a full writeup as I compare the new results to my old ones. For now, suffice it to say that my experience with Ed so far has been nothing but positive.

Now that the mount is (hopefully) performing more up to its designed specification, I'll take the time to get the periodic error correction fully trained again as well as learning to drift align the mount. If time permits, I may use this opportunity as well to try and quantify how well the Celestron All Star Polar Alignment routine performs in comparison to drift alignment. I'll put PemPro through its paces for both periodic error and drift alignment. Then I'll work to nail down the autoguiding to get truly round stars. After that, who knows. But stay tuned - it's sure to be even more fun than it's been already. To close, here's my last astrophoto from my first year - another shot of M42.